Recent headlines have celebrated a potential turning point in America’s obesity epidemic, pointing to declining obesity rates in recent (post-2020) data. The story seems simple: new GLP-1 inhibitor drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy are finally giving us a medical solution to obesity. Yet with just 6% of the population currently taking these medications, could they really be driving this nationwide shift?

A closer look at the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data reveals a more complicated story—one challenges both the optimistic headlines and our growing faith in pharmaceutical solutions. While some groups are indeed getting healthier, others are being left behind, suggesting that our focus on treatment might be coming at the expense of prevention.

The Surface-level Story

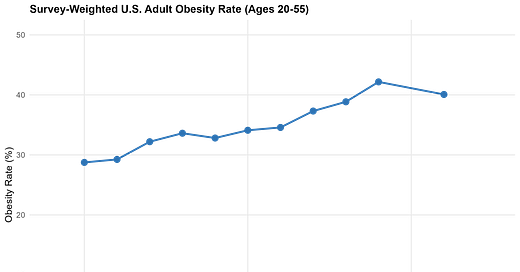

Let’s start with the headline numbers. As reported by the Financial Times, the overall adult obesity rate showed a small decline in the most recent NHANES data. While this would seem to be a cause for celebration, it is important to keep in mind that there was a similar slight decline in the mid-2000s that never materialized.

Before diving deeper into these trends, it's worth noting a key caveat: NHANES data, like any survey, is subject to sampling error. Moreover, the way people respond to health surveys may have changed systematically over time, particularly after COVID-19 disrupted normal data collection procedures.1 It’s important to keep these methodological limitations in mind when interpreting the results.

Note also that the code to reproduce all of these graphs is publicly available here.

Beyond the Averages: Three troubling trends

1. The heaviest Americans are getting heavier

While the median BMI shows a slight decline, the 95th percentile continues to rise. In other words, while some Americans are getting healthier, those struggling most with obesity seem to not be improving.

Equivalently, one can see this by overlaying the BMI distributions from 2018 and 2022—areas with blue sticking out above the purple are excess mass in 2022 relative to 2018; red is the opposite. There is considerable excess mass in the mid-20s of BMI, but there is also excess mass at the high 40s and low 50s of BMI.

2. Young Millennials and Gen Z are seeing the biggest changes

The decline in obesity rates also isn’t uniform across age groups. Adults over 50 (roughly, Gen X) continue to see increasing rates, while the biggest reductions came from those in their 20s and 30s (Gen Z and young Millennials).

Notably, these younger age groups are also the most likely to report using GLP-1 agonist drugs for weight loss. However, recent research in The Lancet raises important concerns about these medications: they can cause substantial muscle loss, with 25%-39% of total weight loss coming from muscle tissue rather than fat. This rate of muscle loss is several times greater than normal age-related decline, raising serious questions about the drugs’ long-term health implications.

3. Youth crisis

Perhaps most worryingly, while adult statistics dominate the headlines, obesity among children and youth has reached new heights. This suggests that while we may be seeing some progress in treating adult obesity, we’re failing to prevent it in the first place.

A Complicated Path Forward

So what explains these divergent trends? The GLP-1 story appears compelling, given that the groups with the highest reported usage rates show the greatest decline in obesity.

Yet it’s difficult to declare victory when obesity among children and youth is out of control and the heaviest people continue to get heavier.

While GLP-1 drugs show remarkable promise—they’re even credited with singlehandedly driving Denmark’s economic growth—we should question whether pharmaceutical intervention is the right path forward, especially for young children. In this case, an ounce of prevention (addressing issues with the food supply) would be worth more than a pound of cure (doubling down on GLP-1 drugs).

However, as my academic research has shown, fixing problems with the food supply is an extremely difficult collective action problem—one that may prove even more challenging than developing new drugs.

I thank Lyman Stone on X for making this point. (Raw link to his post here: https://x.com/lymanstoneky/status/1860887262961000861)